Vitruvian Man

Vitruvian Man

| Vitruvian Man | |

|---|---|

| Italian: L'uomo vitruviano | |

| |

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Year | c. 1490 |

| Type | Pen and ink with wash over metalpoint on paper |

| Dimensions | 34.6 cm × 25.5 cm (13.6 in × 10.0 in) |

| Location | Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice, Italy |

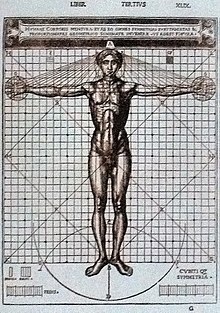

The Vitruvian Man (Italian: L'uomo vitruviano [ˈlwɔːmo vitruˈvjaːno]; originally known as Le proporzioni del corpo umano secondo Vitruvio, lit. 'The proportions of the human body according to Vitruvius') is a drawing made by the Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci in about 1490.[1] It is accompanied by notes based on the work of the Roman architect Vitruvius. The drawing, which is in ink on paper, depicts a man in two superimposed positions with his arms and legs apart and inscribed in a circle and square.

The drawing represents Leonardo's concept of the ideal human body proportions. Its inscription in a square and a circle comes from a description by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise De architectura. Yet, as has been demonstrated, Leonardo did not represent Vitruvius's proportions of the limbs but rather included those he found himself after measuring male models in Milan.[2] While the drawing is named after Vitruvius, some scholars today question the appropriateness of such a title, given that it was first used in the 1490s.[2]

First published in reproduction in 1810, the drawing did not attain its present fame until further reproduced in the later 19th century, and it is not clear that it influenced artistic practice in Leonardo's day or later. It is kept in the Gabinetto dei disegni e delle stampe of the Gallerie dell'Accademia, in Venice, Italy, under reference 228. Like most works on paper, it is displayed to the public only occasionally, so it is not part of the normal exhibition of the museum.[3][4] The work was recently on display at the Louvre's exhibit of Leonardo's work, from 24 October 2019 to 24 February 2020 as part of an agreement between France and Italy.[5][6]

Subject and title[edit]

Leonardo's image demonstrates the blend of mathematics and art during the Renaissance and demonstrates his deep understanding of proportion. In addition, the picture represents a cornerstone of his attempts to relate man to nature. Encyclopædia Britannica online states, "Leonardo envisaged the great picture chart of the human body he had produced through his anatomical drawings and Vitruvian Man as a cosmografia del minor mondo (cosmography of the microcosm). He believed the workings of the human body to be an analogy for the workings of the universe."[7]

According to Leonardo's accompanying text, written in mirror writing,[8] it was made as a study of the proportions of the (male) human body as described in Vitruvius's De architectura 3.1.2–3, which reads:

While Leonardo shows direct knowledge of the work of Vitruvius, his drawing does not follow the description of the ancient text. In drawing the circle and square he observes that the square cannot have the same centre as the circle,[10] but is centered at the groin.[11] This adjustment is the innovative part of Leonardo's drawing and what distinguishes it from earlier illustrations. He also departs from Vitruvius by drawing the arms raised to a position in which the fingertips are level with the top of the head, rather than Vitruvius's much lower angle, in which the arms form lines passing through the navel.

It may be noticed by examining the drawing that the combination of arm and leg positions creates sixteen different poses. The pose with the arms straight out and the feet together is seen to be inscribed in the superimposed square. On the other hand, the spread-eagle pose is seen to be inscribed in the superimposed circle.

Leonardo's collaboration with Luca Pacioli, the author of Divina proportione (Divine Proportion)[12] have led some to speculate that he incorporated the golden ratio in Vitruvian Man, but this is not supported by any of Leonardo's writings,[13][14] and its proportions do not match the golden ratio precisely.[15] Vitruvian Man is likely to have been drawn before Leonardo met Pacioli.

Inspiration and possible collaboration[edit]

Many artists attempted to design figures which would satisfy Vitruvius' claim that a human could fit into both a circle and a square, with the earliest known being by Francesco di Giorgio Martini in the 1480s.[16][17] Leonardo may have been influenced by the work of his friend Giacomo Andrea, an architect and expert on Vitruvius, with whom Leonardo records as having dined in 1490. Leonardo also directly references "Andrea's Vitruvius".[17] Andrea's drawing features erasure marks indicating its unique creation.[17][11] As with Leonardo's Vitruvian Man, Andrea's circle is centered on the navel, but only one pose is included.[11]

Translation of the text[edit]

The text is in two parts, above and below the image.[a][b] The upper part paraphrases Vitruvius:

The lower section of text gives these proportions:

The points determining these proportions are marked with lines on the drawing. Below the drawing is a single line equal to a side of the square and divided into four cubits, of which the outer two are divided into six palms each, two of which have the mirror-text annotation "palmi"; the outermost two palms are divided into four fingers each, and are each annotated "diti".

Provenance[edit]

The drawing was purchased from Gaudenzio de' Pagave by Giuseppe Bossi,[18] who described, discussed and illustrated it in his monograph on Leonardo's The Last Supper, Del Cenacolo di Leonardo da Vinci (1810).[19] The following year he excerpted the section of his monograph concerned with the Vitruvian Man and published it as Delle opinioni di Leonardo da Vinci intorno alla simmetria de' Corpi Umani (1811), with a dedication to his friend Antonio Canova.[20]

After Bossi's death in 1815 the Vitruvian Man was acquired in 1822, along with a number of his drawings, by the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice, Italy, and has remained there since.[21] After the Louvre requested the drawing for a major exhibition of Leonardo's works to open on 24 October 2019, the Italia Nostra argued that the drawing was too fragile to be transported.[22] At a hearing on 16 October 2019, a judge ruled that the group had not proven that the work was too fragile to travel, but set a maximum amount of light for the drawing to be exposed to as well as a subsequent rest period to offset its overall exposure to light. Italy's Minister for Cultural Affairs tweeted that "Now a great cultural operation can start between Italy and France on the two exhibitions about Leonardo in France and Raphael in Rome."[23]

See also[edit]

- Anthropometry – Measurement of the human individual

- Artistic canons of body proportions

- Leonardo's robot

- Modulor – Scale of proportions by Le Corbusier

- T-pose, computer animation term for a pose resembling one of the two postures of the Vitruvian Man

- World in Action – British investigative current affairs TV programme, aired on ITV from 1963 to 1998, used this image as its logo.

Comments

Post a Comment