The TAO

Submerging into THE TAO:

by Ivan C. Possamai 10/22/19

文光塔-二层藻井

1)

Three Treasures (Taoism)

| Part of a series on |

| Daoism |

|---|

|

The Three Treasures or Three Jewels (Chinese: 三寶; pinyin: sānbǎo; Wade–Giles: san-pao) are basic virtues in Taoism. Although the Tao Te Ching originally used sanbao to mean "compassion", "frugality", and "humility", the term was later used to translate the Three Jewels (Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha) in Chinese Buddhism, and to mean the Three Treasures (jing, qi, and shen) in Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Contents

Tao Te Ching[edit source]

Sanbao "three treasures" first occurs in Tao Te Ching chapter 67, which Lin Yutang (1948:292) says contains Laozi's "most beautiful teachings":

Arthur Waley describes these Three Treasures as, "The three rules that formed the practical, political side of the author's teaching (1) abstention from aggressive war and capital punishment, (2) absolute simplicity of living, (3) refusal to assert active authority."

Chinese terminology[edit source]

The first of the Three Treasures is ci (Chinese: 慈; pinyin: cí; Wade–Giles: tz'u; literally: 'compassion, tenderness, love, mercy, kindness, gentleness, benevolence'), which is also a Classical Chinese term for "mother" (with "tender love, nurturing " semantic associations). Tao Te Ching chapters 18 and 19 parallel ci ("parental love") with xiao (孝 "filial love; filial piety"). Wing-tsit Chan (1963:219) believes "the first is the most important" of the Three Treasures, and compares ci with Confucianist ren (仁 "humaneness; benevolence"), which the Tao Te Ching (e.g., chapters 5 and 38) mocks.

The second is jian (儉; jiǎn; chien; 'frugality, moderation, economy, restraint, be sparing'), a practice that the Tao Te Ching (e.g., chapter 59) praises. Ellen M. Chen (1989:209) believes jian is "organically connected" with the Taoist metaphor pu (樸 "uncarved wood; simplicity"), and "stands for the economy of nature that does not waste anything. When applied to the moral life it stands for the simplicity of desire."

The third treasure is a six-character phrase instead of a single word: Bugan wei tianxia xian 不敢為天下先 "not dare to be first/ahead in the world". Chen notes that

In the Mawangdui Silk Texts version of the Tao Te Ching, this traditional "Three Treasures" chapter 67 is chapter 32, following the traditional last chapter (81, 31). Based upon this early silk manuscript, Robert G. Henricks (1989:160) concludes that "Chapters 67, 68, and 69 should be read together as a unit." Besides some graphic variants and phonetic loan characters, like ci (兹 "mat, this") for ci (慈 "compassion, love", clarified with the "heart radical" 心), the most significant difference with the received text is the addition of heng (恆, "constantly, always") with "I constantly have three …" (我恆有三) instead of "I have three …" (我有三).

English translations[edit source]

The language of the Tao Te Ching is notoriously difficult to translate, as illustrated by the diverse English renditions of "Three Treasures" below.

| Translation | Sanbao 三寶 | Ci 慈 | Jian 儉 | Bugan wei tianxia xian 不敢為天下先 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balfour (1884:41) | three things which I regard as precious | compassion | frugality | not venturing to take precedence of others — modesty |

| Legge (1891:110) | three precious things | gentleness | economy | shrinking from taking precedence of others |

| Lin (1948:291) | Three Treasures | Love | Moderation | Never be the first in the world |

| Erkes (1950:117) | three jewels | kindness | thriftiness | not daring to play the first part in the empire |

| Waley (1934:225) | three treasures | pity | frugality | refusal to be 'foremost of all things under heaven' |

| Wu (1961:97) | Three Treasures | Mercy | Frugality | Not daring to be First in the World |

| Chan (1963:219) | three treasures | deep love | frugality | not to dare to be ahead of the world |

| Lau (1963:129) | three treasures | compassion | frugality | not daring to take the lead in the empire |

| English & Feng (1972:n.p.) | three treasures which I hold and keep | mercy | economy | daring not to be ahead of others — humility |

| Wieger & Bryce (1984:34) | three things | charity | simplicity | humility |

| Mitchell (1988:110) | three treasures which I preserve and treasure | compassion | frugality | daring not to be first in the world |

| Henricks (1989:38) | three treasures | compassion | frugality | not presuming to be at the forefront in the world |

| Chen (1989:208) | three treasures | motherly love | frugality | daring not be at the world's front |

| Mair (1990:41) | three treasures | compassion | frugality | not daring to be ahead of all under heaven |

| Muller (2004:n.p.) | three treasures | compassion | frugality | not daring to put myself ahead of everybody |

A consensus translation of the Three Treasures could be: compassion or love, frugality or simplicity, and humility or modesty.

Other meanings[edit source]

In addition to these Taoist "Three Treasures", Chinese sanbao can also refer to the Three Treasures in Traditional Chinese Medicine or the Three Jewels in Buddhism. Victor H. Mair (1990:110) notes that Chinese Buddhists chose the Taoist term sanbao to translate Sanskrit triratna or ratnatraya ("three jewels"), and "It is not at all strange that the Taoists would take over this widespread ancient Indian expression and use it for their own purposes."

Erik Zürcher, who studied influences of Buddhist doctrinal terms in Daoism, noted (1980:115) two later meanings of sanbao: Dao 道 "the Way", jing 經 "the Scriptures", and shi 師 "the Master" seems to be patterned after Buddhist usage; Tianbao jun 天寶君 "Lord of Celestial Treasure", Lingbao jun 靈寶君 "Lord of Numinous Treasure", and Shenbao jun 神寶君 "Lord of Divine Treasure" are the Sanyuan 三元 "Three Primes" of the Lingbao School.

References[edit source]

- Balfour, Frederic H., 1884, Taoist Texts: Ethical, Political, and Speculative, Trubner.

- Chan, Wing-Tsit, 1963, The Way of Lao Tzu, Bobbs-Merrill.

- Chen, Ellen M., 1989, The Te Tao Ching: A New Translation with Commentary, Paragon House.

- English, Jane and Gia-Fu Feng, 1972, Tao Te Ching, Vintage Books.

- Erkes, Eduard, 1950, Ho-Shang-Kung's Commentary on Lao-tse, Artibus Asiae.

- Henricks, Robert G., 1989, Lao-tzu: Te-Tao Ching, A New Translation Based on the Recently Discovered Ma-wang-tui Texts, Ballantine.

- Lau, D.C., 1963, Tao Te Ching, Penguin Books.

- Legge, James, 1891, The Texts of Taoism, 2 vols (Sacred Books of China 39 and 40), Clarendon Press, 1891.

- Lin Yutang, 1948, The Wisdom of Laotse, Random House.

- Mair, Victor H., 1990, Tao Te Ching: The Classic Book of Integrity and the Way, by Lao Tzu; an entirely new translation based on the recently discovered Ma-wang-tui manuscripts, Bantam Books.

- Mitchell, Stephen, 1988, Tao Te Ching, Harper Collins.

- Muller, Charles, 2004, Daode jing.

- Waley, Arthur, 1934, The Way and Its Power: A Study of the Tao Te Ching and its Place in Chinese Thought, Allen & Unwin.

- Wieger, Léon, 1984. Wisdom of the Daoist Masters, tr. Derek Bryce. Llanerch Enterprises.

- Wu, John C.H., 1961, Tao Teh Ching, St. John's University Press.

- Zürcher, Erik, 1980, "Buddhist Influence on Early Taoism: A Survey of Scriptural Evidence," T'oung Pao 66.1/3, pp. 84–147.

2)

A Mapping of the Human Thinking

The computers came from the I ching the Binary system 0 - 1 Ying and Yang

Dated 1300 years before christ, the oldest book in the world.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cwSYbZoa4mk

I Ching

Title page of a Song dynasty (c. 1100) edition of the I Ching

| |

| Original title | 易 *lek [note 1] |

|---|---|

| Country | Zhou dynasty (China) |

| Genre | Divination, cosmology |

| Published | Late 9th century BC |

| I Ching Classic of Changes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

"I (Ching)" in seal script (top),[note 1] Traditional (middle), and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters

| |||

| Traditional Chinese | 易經 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 易经 | ||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Yìjīng | ||

| Literal meaning | "Classic of Changes" | ||

| |||

The I Ching or Yi Jing (Chinese: 易經; pinyin: Yìjīng; Mandarin pronunciation: [î tɕíŋ] ( listen)), also known as Classic of Changes or Book of Changes, is an ancient Chinese divination text and the oldest of the Chinese classics. Possessing a history of more than two and a half millennia of commentary and interpretation, the I Ching is an influential text read throughout the world, providing inspiration to the worlds of religion, psychoanalysis, literature, and art. Originally a divination manual in the Western Zhou period (1000–750 BC), over the course of the Warring States period and early imperial period (500–200 BC) it was transformed into a cosmological text with a series of philosophical commentaries known as the "Ten Wings".[1] After becoming part of the Five Classics in the 2nd century BC, the I Ching was the subject of scholarly commentary and the basis for divination practice for centuries across the Far East, and eventually took on an influential role in Western understanding of Eastern thought.

listen)), also known as Classic of Changes or Book of Changes, is an ancient Chinese divination text and the oldest of the Chinese classics. Possessing a history of more than two and a half millennia of commentary and interpretation, the I Ching is an influential text read throughout the world, providing inspiration to the worlds of religion, psychoanalysis, literature, and art. Originally a divination manual in the Western Zhou period (1000–750 BC), over the course of the Warring States period and early imperial period (500–200 BC) it was transformed into a cosmological text with a series of philosophical commentaries known as the "Ten Wings".[1] After becoming part of the Five Classics in the 2nd century BC, the I Ching was the subject of scholarly commentary and the basis for divination practice for centuries across the Far East, and eventually took on an influential role in Western understanding of Eastern thought.

The I Ching uses a type of divination called cleromancy, which produces apparently random numbers. Six numbers between 6 and 9 are turned into a hexagram, which can then be looked up in the I Ching book, arranged in an order known as the King Wen sequence. The interpretation of the readings found in the I Ching is a matter of centuries of debate, and many commentators have used the book symbolically, often to provide guidance for moral decision making as informed by Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism. The hexagrams themselves have often acquired cosmological significance and paralleled with many other traditional names for the processes of change

Taoism tends to emphasize various themes of the Tao Te Ching and Zhuangzi, such as naturalness, spontaneity, simplicity, detachment from desires, and most important of all, wu wei.[45] However, the concepts of those keystone texts cannot be equated with Taoism as a whole.[46]

| 1 乾 (qián) | 2 坤 (kūn) | 3 屯 (zhūn) | 4 蒙 (méng) | 5 需 (xū) | 6 訟 (sòng) | 7 師 (shī) | 8 比 (bǐ) |

| 9 小畜 (xiǎo chù) | 10 履 (lǚ) | 11 泰 (tài) | 12 否 (pǐ) | 13 同人 (tóng rén) | 14 大有 (dà yǒu) | 15 謙 (qiān) | 16 豫 (yù) |

| 17 隨 (suí) | 18 蠱 (gŭ) | 19 臨 (lín) | 20 觀 (guān) | 21 噬嗑 (shì kè) | 22 賁 (bì) | 23 剝 (bō) | 24 復 (fù) |

| 25 無妄 (wú wàng) | 26 大畜 (dà chù) | 27 頤 (yí) | 28 大過 (dà guò) | 29 坎 (kǎn) | 30 離 (lí) | 31 咸 (xián) | 32 恆 (héng) |

| 33 遯 (dùn) | 34 大壯 (dà zhuàng) | 35 晉 (jìn) | 36 明夷 (míng yí) | 37 家人 (jiā rén) | 38 睽 (kuí) | 39 蹇 (jiǎn) | 40 解 (xiè) |

| 41 損 (sǔn) | 42 益 (yì) | 43 夬 (guài) | 44 姤 (gòu) | 45 萃 (cuì) | 46 升 (shēng) | 47 困 (kùn) | 48 井 (jǐng) |

| 49 革 (gé) | 50 鼎 (tǐng) | 51 震 (zhèn) | 52 艮 (gèn) | 53 漸 (jiàn) | 54 歸妹 (guī mèi) | 55 豐 (fēng) | 56 旅 (lǚ) |

| 57 巽 (xùn) | 58 兌 (duì) | 59 渙 (huàn) | 60 節 (jié) | 61 中孚 (zhōng fú) | 62 小過 (xiǎo guò) | 63 既濟 (jì jì) | 64 未濟 (wèi jì) |

3)

Shen Buhai

| Shen Buhai | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 申不害 | ||

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese legalism |

|---|

|

Shen Buhai (Chinese: 申不害; c. 400 BC – c. 337 BC)[1] was a Chinese essayist, philosopher, and politician. He served as Chancellor of the Han state under Marquis Zhao of Han for fifteen years, from 354 BC to 337 BC.[2] A contemporary of syncretist Shi Jiao and Legalist Shang Yang, he was born in the State of Zheng, and was likely a minor official there. After Han conquered Zheng in 375 BC, he rose up in the ranks of the Han officialdom, dividing up its territories and successfully reforming it. Though not dealing in penal law himself, his administrative innovations would be incorporated into "Chinese Legalist" statecraft by Han Fei, his most famous successor, and Shen Buhai's book most resembles the Han Feizi (though more conciliatory). He died of natural causes while in office.

Though Chinese administration cannot be traced to any one individual, emphasizing a merit system figures like 4th century BC reformer Shen Buhai may have had more influence than any other, and might be considered its founder, if not valuable as a rare pre-modern example of abstract theory of administration. Sinologist Herrlee G. Creel sees in Shen Buhai the "seeds of the civil service examination", and, if one wished to exaggerate, the first political scientist,[3] while the correlation between Shen's conception of the inactive (Wu-wei) ruler and the handling of claims and titles likely informed the Taoist conception of the formless Tao (name that cannot be named) that "gives rise to the ten thousand things."[4] He is attributed the dictum "The Sage ruler relies on standards and does not rely on wisdom; he relies on technique, not on persuasions."[5]

4)

Realpolitik

Realpolitik (from German: real; "realistic", "practical", or "actual"; and Politik; "politics", German pronunciation: [ʁeˈaːlpoliˌtiːk]) is politics or diplomacy based primarily on considerations of given circumstances and factors, rather than explicit ideological notions or moral and ethical premises. In this respect, it shares aspects of its philosophical approach with those of realism and pragmatism. It is often simply referred to as "pragmatism" in politics, e.g. "pursuing pragmatic policies". The term Realpolitik is sometimes used pejoratively to imply politics that are perceived as coercive, amoral, or Machiavellian.[1]

5)

Zhuangzi (book)

The Butterfly Dream, by Chinese painter Lu Zhi (c. 1550)

| |

| Author | (trad.) Zhuang Zhou |

|---|---|

| Original title | 莊子 |

| Country | China |

| Language | Classical Chinese |

| Genre | Philosophy |

Publication date

| c. 3rd century BC |

| Zhuangzi | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Traditional Chinese | 莊子 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 庄子 | ||

| Literal meaning | "[The Writings of] Master Zhuang" | ||

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| Daoism |

|---|

|

The Zhuangzi (Mandarin: [ʈʂwáŋ.tsɹ̩̀]; historically romanized Chuang Tzŭ) is an ancient Chinese text from the late Warring States period (476–221 BC) which contains stories and anecdotes that exemplify the carefree nature of the ideal Daoist sage. Named for its traditional author, "Master Zhuang" (Zhuangzi), the Zhuangzi is—along with the Tao Te Ching—one of the two foundational texts of Taoism, and is generally considered the most important of all Daoist writings.

The Zhuangzi consists of a large collection of anecdotes, allegories, parables, and fables, which are often humorous or irreverent in nature. Its main themes are of spontaneity in action and of freedom from the human world and its conventions. The fables and anecdotes in the text attempt to illustrate the falseness of human distinctions between good and bad, large and small, life and death, and human and nature. While other ancient Chinese philosophers focused on moral and personal duty, Zhuangzi promoted carefree wandering and becoming one with "the Way" (Dào 道) by following nature.

Though primarily known as a philosophical work, the Zhuangzi is regarded as one of the greatest literary works in all of Chinese history, and has been called "the most important pre-Qin text for the study of Chinese literature." A masterpiece of both philosophical and literary skill, it has significantly influenced writers for more than 2000 years from the Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 220) to the present. Many major Chinese writers and poets in history—such as Sima Xiangru and Sima Qian during the Han dynasty, Ruan Ji and Tao Yuanming during the Six Dynasties (222–589), Li Bai during the Tang dynasty (618–907), and Su Shi and Lu You in the Song dynasty (960–1279)—were heavily influenced by the Zhuangzi.

Content[edit source]

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern philosophy |

|---|

|

The Zhuangzi consists of a large collection of anecdotes, allegories, parables, and fables, which are often humorous or irreverent in nature.[16] Most Zhuangzi stories are fairly short and simple, such as "Lickety" and "Split" drilling seven holes in "Wonton" (chapter 7) or Zhuangzi being discovered sitting and drumming on a basin after his wife dies (chapter 18), although a few are longer and more complex, like the story of Master Lie and the magus (chapter 14) and the account of the Yellow Emperor's music (chapter 14).[16] Unlike the other stories and allegories in other pre-Qin texts, the Zhuangzi is unique in that the allegories form the bulk of the text, rather than occasional features, and are always witty, emotional, and are not limited to reality.[16]

Unlike other ancient Chinese works, whose allegories were usually based on historical legends and proverbs, most Zhuangzi stories seem to have been invented by Zhuangzi himself. Some are completely whimsical, such as the strange description of evolution from "misty spray" through a series of substances and insects to horses and humans (chapter 18), while a few other passages seem to be "sheer playful nonsense" which read like Lewis Carroll's "Jabberwocky".[17] The Zhuangzi is full of quirky and fantastic characters, such as "Mad Stammerer", "Fancypants Scholar", "Sir Plow", and a man who believes his left arm will turn into a rooster, his right arm will turn into a crossbow, and his buttocks will become cartwheels.[18]

A master of language, Zhuangzi sometimes engages in logic and reasoning, but then turns it upside down or carries the arguments to absurdity to demonstrate the limitations of human knowledge and the rational world.[18] Some of Zhuangzi's reasoning, such as his renowned argument with his philosopher friend Huizi (Master Hui) about the joy of fish (chapter 17), have been compared to the Socratic and Platonic dialogue traditions, and Huizi's paradoxes near the end of the book have been termed "strikingly like those of Zeno of Elea."[18]

Notable passages[edit source]

"The Butterfly Dream"[edit source]

The most famous of all Zhuangzi stories—"Zhuang Zhou Dreams of Being a Butterfly"—appears at the end of the second chapter, "On the Equality of Things".

The well-known image of Zhuangzi wondering if he was a man who dreamed of being a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming of being a man is so striking that whole dramas have been written on its theme.[20] In it Zhuangzi "[plays] with the theme of transformation",[20] illustrating that "the distinction between waking and dreaming is another false dichotomy. If [one] distinguishes them, how can [one] tell if [one] is now dreaming or awake?"[21]

"The Death of Wonton"[edit source]

Another well known Zhuangzi story—"The Death of Wonton"—illustrates the dangers Zhuangzi saw in going against the innate nature of things.[22]

Zhuangzi believed that the greatest of all human happiness could be achieved through a higher understanding of the nature of things, and that in order to develop oneself fully one needed to express one's innate ability.[20] In this anecdote, Mair suggests that Zhuangzi humorously and absurdly uses "Wonton"—a name for both the Chinese conception of primordial chaos and, by later physical analogy, wonton soup—to demonstrate what he believed were the disastrous consequences of going against things' innate natures.

"The Debate on the Joy of Fish"[edit source]

The story of "The Debate on the Joy of Fish" is a well-known anecdote that has been compared to the Socratic dialogue tradition of ancient Greece.[18]

The exact point made by Zhuangzi in this debate is not entirely clear.[25] The story seems to make the point that "knowing" a thing is simply a state of mind, and that it is not possible to determine if that knowing has any objective validity.[26] This story has been cited as an example of Zhuangzi's linguistic mastery, as he subtly uses reason to make an anti-rationalist point.[26]

"Drumming On a Tub and Singing"[edit source]

Another well-known Zhuangzi story—"Drumming On a Tub and Singing"—describes how Zhuangzi did not view death as something to be feared.

Zhuangzi seems to have viewed death as a natural process or transformation, where one gives up one form of existence and assumes another.[28] In the second chapter, he makes the point that, for all humans know, death may in fact be better than life: "How do I know that loving life is not a delusion? How do I know that in hating death I am not like a man who, having left home in his youth, has forgotten the way back?"[29] His writings teach that "the wise man or woman accepts death with equanimity and thereby achieves absolute happiness."[28]

Zhuangzi's death[edit source]

The story of Zhuangzi's death, contained in chapter 32 of the text, exemplifies the colorful lore that grew up around Zhuangzi in the decades after his death, as well as the elaboration of the core philosophical ideas contained in the "inner chapters" that appears in the "outer" and "miscellaneous chapters".[9]

Influence[edit source]

The Zhuangzi is by far the most influential purely literary work dating from before China's imperial unification in 221 BC.[38] Its literary quality, imagination and creativity, and linguistic prowess were entirely unprecedented in the period of its creation.[38] Virtually every major Chinese writer or poet in history, from Sima Xiangru and Sima Qian during the Han dynasty, Ruan Ji and Tao Yuanming during the Six Dynasties, Li Bai during the Tang dynasty, to Su Shi and Lu You in the Song dynasty were "deeply imbued with the ideas and artistry of the Zhuangzi."[39]

Modern[edit source]

Outside of China and the traditional "Sinosphere", the Zhuangzi lags far behind the Tao Te Ching in general popularity, and is rarely known by non-scholars.[36] A number of prominent scholars have attempted to bring the Zhuangzi to wider attention among Western readers. In 1939, the British translator and Sinologist Arthur Waley described the Zhuangzi as "one of the most entertaining as well as one of the profoundest books in the world."[46] In the introduction to his 1994 translation of the Zhuangzi, the American Sinologist Victor H. Mair wrote: "I feel a sense of injustice that the Dao De Jing is so well known to my fellow citizens while the Zhuangzi is so thoroughly ignored, because I firmly believe that the latter is in every respect a superior work."[37]

6)

Neidan

| Part of a series on |

| Daoism |

|---|

|

| showNeidan |

|---|

Neidan, or internal alchemy (simplified Chinese: 內丹术; traditional Chinese: 內丹術; pinyin: nèidān shù), is an array of esoteric doctrines and physical, mental, and spiritual practices that Taoist initiates use to prolong life and create an immortal spiritual body that would survive after death (Skar and Pregadio 2000, 464). Also known as Jindan (金丹 "golden elixir"), inner alchemy combines theories derived from external alchemy (waidan 外丹), correlative cosmology (including the Five Phases), the emblems of the Yijing, and medical theory, with techniques of Daoist meditation, daoyin gymnastics, and sexual hygiene (Baldrian-Hussein 2008, 762).

In Neidan the human body becomes a cauldron (or "ding") in which the Three Treasures of Jing ("Essence"), Qi ("Breath") and Shen ("Spirit") are cultivated for the purpose of improving physical, emotional and mental health, and ultimately returning to the primordial unity of the Tao, i.e., becoming an Immortal. It is believed the Xiuzhen Tu is such a cultivation map. In China, it is an important form of practice for most schools of Taoism.

The Three Treasures[edit source]

Internal alchemy focuses upon transforming the bodily sanbao "three treasures", which are the essential energies sustaining human life:

- Jing 精 "nutritive essence, essence; refined, perfected; extract; spirit, demon; sperm, seed"

- Qi 氣 "vitality, energy, force; air, vapor; breath; spirit, vigor; attitude"

- Shen 神 "spirit; soul, mind; god, deity; supernatural being"

According to the 13th-century Book of Balance and Harmony:

- Making one's essence complete, one can preserve the body. To do so, first keep the body at ease, and make sure there are no desires. Thereby energy can be made complete.

- Making one's energy complete, one can nurture the mind. To do so, first keep the mind pure, and make sure there are no thoughts. Thereby spirit can be made complete.

- Making one's spirit complete, one can recover emptiness. To do so, first keep the will sincere, and make sure body and mind are united. Thereby spirit can be returned to emptiness. ... To attain immortality, there is nothing else but the refinement of these three treasures: essence, energy, spirit." (tr. Kohn 1956, 146).

When the "three treasures" are internally maintained, along with a balance of yin and yang, it is possible to achieve a healthy body and longevity, which are the main goals of internal alchemy (Ching 1996, 395).

Jing[edit source]

Jing "essence" referring to the energies of the physical body. Based upon the idea that death was caused by depleting one's jing, Daoist internal alchemy claimed that preserving jing allowed one to achieve longevity, if not immortality. (Schipper 1993, 154).

Qi[edit source]

Qi or ch'i is defined as the "natural energy of the universe" and manifests in everyone and everything (Carroll 2008). By means of internal alchemy, Taoists strive to obtain a positive flow of qi through the body in paths moving to each individual organ (Smith 1986, 201).

Healing practices such as acupuncture, massage, cupping and herbal medicines are believed to open up the qi meridians throughout the body so that the qi can flow freely. Keeping qi in balance and flowing throughout the body promotes health; imbalance can lead to sickness.

Shen[edit source]

Shen is the original spirit of the body. Taoists try to become conscious of shen through meditation (Smith 1986, 202).

7)

Way of the Celestial Masters

(Redirected from Celestial Masters)

| Way of the Celestial Masters | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 天師道 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 天师道 | ||

| |||

The Way of the Celestial Masters is a Chinese Daoist movement that was founded by Zhang Daoling in 142 CE.[1] At its height, the movement controlled a theocratic state in what is now Sichuan.

8) School of Naturalists

The School of Naturalists or the School of Yin-yang (陰陽家/阴阳家; Yīnyángjiā; Yin-yang-chia; "School of Yin-Yang") was a Warring States-era philosophy that synthesized the concepts of yin-yang and the Five Elements.

9)

Wuxing (Chinese philosophy)

(Redirected from Five Phases)

| Wuxing | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 五行 | ||

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| Daoism |

|---|

|

| Classical elements |

|---|

Stoicheion (στοιχεῖον)

|

Wuxing (五行)

|

Godai (五大)

|

Bön

|

Alchemy

|

The wuxing (Chinese: 五行; pinyin: wǔxíng), also known as the Five Elements, Five Phases, the Five Agents, the Five Movements, Five Processes, the Five Steps/Stages and the Five Planets of significant gravity (Mars: 火, Mercury: 水, Jupiter: 木, Venus: 金, and Saturn: 土),[1] is the short form of "Wǔ zhǒng liúxíng zhī qì" (五種流行之氣) or "the five types of chi dominating at different times".[2] It is a fivefold conceptual scheme that many traditional Chinese fields used to explain a wide array of phenomena, from cosmic cycles to the interaction between internal organs, and from the succession of political regimes to the properties of medicinal drugs. The "Five Phases" are Wood (木 mù), Fire (火 huǒ), Earth (土 tǔ), Metal (金 jīn), and Water (水 shuǐ). This order of presentation is known as the "mutual generation" (相生 xiāngshēng) sequence. In the order of "mutual overcoming" (相剋/相克 xiāngkè), they are Wood, Earth, Water, Fire, and Metal.[3][4][5]

The system of five phases was used for describing interactions and relationships between phenomena. After it came to maturity in the second or first century BCE during the Han dynasty, this device was employed in many fields of early Chinese thought, including seemingly disparate fields such as geomancy or Feng shui, astrology, traditional Chinese medicine, music, military strategy, and martial arts. The system is still used as a reference in some forms of complementary and alternative medicine and martial arts.

Contents

Names[edit source]

Xing (行) of wuxing means moving; a planet is called a 'moving star' (行星) in Chinese. Wu Xing (五行) originally refers to the five major planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Mercury, Mars, Venus) that create five dimensions of earth life.[1] Wuxing is also widely translated as "Five Elements" and this is used extensively by many including practitioners of Five Element acupuncture. This translation arose by false analogy with the Western system of the four elements.[6] Whereas the classical Greek elements were concerned with substances or natural qualities, the Chinese xíng are "primarily concerned with process and change," hence the common translation as "phases" or "agents".[7] By the same token, Mù is thought of as "Tree" rather than "Wood".[8] The word 'element' is thus used within the context of Chinese medicine with a different meaning to its usual meaning.

It should be recognized that the word phase, although commonly preferred, is not perfect. Phase is a better translation for the five seasons (五運 Wǔ Yùn) mentioned below, and so agents or processes might be preferred for the primary term xíng. Manfred Porkert attempts to resolve this by using Evolutive Phase for 五行 Wǔ Xíng and Circuit Phase for 五運 Wǔ Yùn, but these terms are unwieldy.

Some of the Mawangdui Silk Texts (no later than 168 BC) also present the wuxing as "five virtues" or types of activities.[9] Within Chinese medicine texts the wuxing are also referred to as Wu Yun (五運}}; wǔ yùn) or a combination of the two characters (Wu Xing-Yun) these emphasise the correspondence of five elements to five 'seasons' (four seasons plus one). Another tradition refers to the Wǔ Xíng as Wǔ Dé (五德), the Five Virtues.

The phases[edit source]

The five phases are around 72 days each and are usually used to describe the state in nature:

- Wood/Spring: a period of growth, which generates abundant wood and vitality

- Fire/Summer: a period of swelling, flowering, brimming with fire and energy

- Earth: the in-between transitional seasonal periods, or a separate 'season' known as Late Summer or Long Summer - in the latter case associated with leveling and dampening (moderation) and fruition

- Metal/Autumn: a period of harvesting and collecting

- Water/Winter: a period of retreat, where stillness and storage pervades

Cycles[edit source]

The doctrine of five phases describes two cycles, a generating or creation (生, shēng) cycle, also known as "mother-son", and an overcoming or destruction (剋/克, kè) cycle, also known as "grandfather-grandson", of interactions between the phases. Within Chinese medicine the effects of these two main relations are further elaborated:

- Inter-promoting (shēng cycle, mother/son)

- Interacting (grandmother/grandson)

- Overacting (kè cycle, grandfather/grandson)

- Counteracting (reverse kè)

Generating[edit source]

The common memory jogs, which help to remind in what order the phases are:

- Wood feeds Fire

- Fire creates Earth (ash)

- Earth bears Metal

- Metal collects Water

- Water nourishes Wood

Other common words for this cycle include "begets", "engenders" and "mothers".

Overcoming[edit source]

- Wood parts Earth (such as roots or trees can prevent soil erosion)

- Earth dams (or muddies or absorbs) Water

- Water extinguishes Fire

- Fire melts Metal

- Metal chops Wood

This cycle might also be called "controls", "restrains" or "fathers".

Cosmology and feng shui[edit source]

According to wuxing theory, the structure of the cosmos mirrors the five phases. Each phase has a complex series of associations with different aspects of nature, as can be seen in the following table. In the ancient Chinese form of geomancy, known as Feng Shui, practitioners all based their art and system on the five phases (wuxing). All of these phases are represented within the trigrams. Associated with these phases are colors, seasons and shapes; all of which are interacting with each other.[10]

Based on a particular directional energy flow from one phase to the next, the interaction can be expansive, destructive, or exhaustive. A proper knowledge of each aspect of energy flow will enable the Feng Shui practitioner to apply certain cures or rearrangement of energy in a way they believe to be beneficial for the receiver of the Feng Shui Treatment.

| Movement | Metal | Metal | Fire | Wood | Wood | Water | Earth | Earth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trigram hanzi | 乾 | 兌 | 離 | 震 | 巽 | 坎 | 艮 | 坤 |

| Trigram pinyin | qián | duì | lí | zhèn | xùn | kǎn | gèn | kūn |

| Trigrams | ☰ | ☱ | ☲ | ☳ | ☴ | ☵ | ☶ | ☷ |

| I Ching | Heaven | Lake | Fire | Thunder | Wind | Water | Mountain | Field |

| Planet (Celestial Body) | Neptune | Venus | Mars | Jupiter | Pluto | Mercury | Uranus | Saturn |

| Color | Indigo | White | Crimson | Green | Scarlet | Black | Purple | Yellow |

| Day | Friday | Friday | Tuesday | Thursday | Thursday | Wednesday | Saturday | Saturday |

| Season | Autumn | Autumn | Summer | Spring | Spring | Winter | Intermediate | Intermediate |

| Cardinal direction | West | West | South | East | East | North | Center | Center |

Dynastic transitions[edit source]

According to the Warring States period political philosopher Zou Yan 鄒衍 (c. 305–240 BCE), each of the five elements possesses a personified "virtue" (de 德), which indicates the foreordained destiny (yun 運) of a dynasty; accordingly, the cyclic succession of the elements also indicates dynastic transitions. Zou Yan claims that the Mandate of Heaven sanctions the legitimacy of a dynasty by sending self-manifesting auspicious signs in the ritual color (yellow, blue, white, red, and black) that matches the element of the new dynasty (Earth, Wood, Metal, Fire, and Water). From the Qin dynasty onward, most Chinese dynasties invoked the theory of the Five Elements to legitimize their reign.[11]

Chinese medicine[edit source]

The interdependence of zang-fu networks in the body was said to be a circle of five things, and so mapped by the Chinese doctors onto the five phases.[12][13]

| Movement | Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planet | Jupiter | Mars | Saturn | Venus | Mercury |

| Mental Quality | idealism, spontaneity, curiosity | passion, intensity | agreeableness, honesty | intuition, rationality, mind | erudition, resourcefulness, wit |

| Emotion | anger, kindness | hate, resolve | anxiety, joy | grief, bravery | fear, gentleness |

| Zang (yin organs) | liver | heart/pericardium | spleen/pancreas | lung | kidney |

| Fu (yang organs) | gall bladder | small intestine/San Jiao | stomach | large intestine | urinary bladder |

| Sensory Organ | eyes | tongue | mouth | nose | ears |

| Body Part | tendons | pulse | muscles | skin | bones |

| Body Fluid | tears | sweat | saliva | mucus | urine |

| Finger | index finger | middle finger | thumb | ring finger | pinky finger |

| Sense | sight | taste | touch | smell | hearing |

| Taste[14] | sour | bitter | sweet | pungent, umami | salty |

| Smell | rancid | scorched | fragrant | rotten | putrid |

| Life | early childhood | pre-puberty | adolescence/intermediate | adulthood | old age, conception |

| Animal | scaly | feathered | human | furred | shelled |

| Hour | 3-9 | 9-15 | change | 15-21 | 21-3 |

| Year | Spring Equinox | Summer Solstice | Change | Fall Equinox | Winter Solstice |

| 360° | 45-135° | 135-225° | Change | 225-315° | 315-45° |

Celestial stem[edit source]

| Movement | Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavenly Stem | Jia 甲 Yi 乙 | Bing 丙 Ding 丁 | Wu 戊 Ji 己 | Geng 庚 Xin 辛 | Ren 壬 Gui 癸 |

| Year ends with | 4, 5 | 6, 7 | 8, 9 | 0, 1 | 2, 3 |

Ming neiyin[edit source]

In Ziwei, neiyin (纳音) or the method of divination is the further classification of the Five Elements into 60 ming (命), or life orders, based on the ganzhi. Similar to the astrology zodiac, the ming is used by fortune-tellers to analyse a person's personality and future fate.

| Order | Ganzhi | Ming | Order | Ganzhi | Ming | Element |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jia Zi 甲子 | Sea metal 海中金 | 31 | Jia Wu 甲午 | Sand metal 沙中金 | Metal |

| 2 | Yi Chou 乙丑 | 32 | Yi Wei 乙未 | |||

| 3 | Bing Yin 丙寅 | Furnace fire 炉中火 | 33 | Bing Shen 丙申 | Forest fire 山下火 | Fire |

| 4 | Ding Mao 丁卯 | 34 | Ding You 丁酉 | |||

| 5 | Wu Chen 戊辰 | Forest wood 大林木 | 35 | Wu Xu 戊戌 | Meadow wood 平地木 | Wood |

| 6 | Ji Si 己巳 | 36 | Ji Hai 己亥 | |||

| 7 | Geng Wu 庚午 | Road earth 路旁土 | 37 | Geng Zi 庚子 | Adobe earth 壁上土 | Earth |

| 8 | Xin Wei 辛未 | 38 | Xin Chou 辛丑 | |||

| 9 | Ren Shen 壬申 | Sword metal 剑锋金 | 39 | Ren Yin 壬寅 | Precious metal 金白金 | Metal |

| 10 | Gui You 癸酉 | 40 | Gui Mao 癸卯 | |||

| 11 | Jia Xu 甲戌 | Volcanic fire 山头火 | 41 | Jia Chen 甲辰 | Lamp fire 佛灯火 | Fire |

| 12 | Yi Hai 乙亥 | 42 | Yi Si 乙巳 | |||

| 13 | Bing Zi 丙子 | Cave water 洞下水 | 43 | Bing Wu 丙午 | Sky water 天河水 | Water |

| 14 | Ding Chou 丁丑 | 44 | Ding Wei 丁未 | |||

| 15 | Wu Yin 戊寅 | Fortress earth 城头土 | 45 | Wu Shen 戊申 | Highway earth 大驿土 | Earth |

| 16 | Ji Mao 己卯 | 46 | Ji You 己酉 | |||

| 17 | Geng Chen 庚辰 | Wax metal 白腊金 | 47 | Geng Xu 庚戌 | Jewellery metal 钗钏金 | Metal |

| 18 | Xin Si 辛巳 | 48 | Xin Hai 辛亥 | |||

| 19 | Ren Wu 壬午 | Willow wood 杨柳木 | 49 | Ren Zi 壬子 | Mulberry wood 桑柘木 | Wood |

| 20 | Gui Wei 癸未 | 50 | Gui Chou 癸丑 | |||

| 21 | Jia Shen 甲申 | Stream water 泉中水 | 51 | Jia Yin 甲寅 | Rapids water 大溪水 | Water |

| 22 | Yi You 乙酉 | 52 | Yi Mao 乙卯 | |||

| 23 | Bing Xu 丙戌 | Roof tiles earth 屋上土 | 53 | Bing Chen 丙辰 | Desert earth 沙中土 | Earth |

| 24 | Ding Hai 丁亥 | 54 | Ding Si 丁巳 | |||

| 25 | Wu Zi 戊子 | Lightning fire 霹雳火 | 55 | Wu Wu 戊午 | Sun fire 天上火 | Fire |

| 26 | Ji Chou 己丑 | 56 | Ji Wei 己未 | |||

| 27 | Geng Yin 庚寅 | Conifer wood 松柏木 | 57 | Geng Shen 庚申 | Pomegranate wood 石榴木 | Wood |

| 28 | Xin Mao 辛卯 | 58 | Xin You 辛酉 | |||

| 29 | Ren Chen 壬辰 | River water 长流水 | 59 | Ren Xu 壬戌 | Ocean water 大海水 | Water |

| 30 | Gui Si 癸巳 | 60 | Gui Hai 癸亥 |

Music[edit source]

The Yuèlìng chapter (月令篇) of the Lǐjì (禮記) and the Huáinánzǐ (淮南子) make the following correlations:

| Movement | Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colour | Green | Red | Yellow | White | Black |

| Arctic Direction | east | south | center | west | north |

| Basic Pentatonic Scale pitch | 角 | 徵 | 宮 | 商 | 羽 |

| Basic Pentatonic Scale pitch pinyin | jué | zhǐ | gōng | shāng | yǔ |

| solfege | mi or E | sol or G | do or C | re or D | la or A |

- The Chinese word 青 qīng, has many meanings, including green, azure, cyan, and black. It refers to green in wuxing.

- In most modern music, various five note or seven note scales (e.g., the major scale) are defined by selecting five or seven frequencies from the set of twelve semi-tones in the Equal tempered tuning. The Chinese "lǜ" tuning is closest to the ancient Greek tuning of Pythagoras.

Martial arts[edit source]

T'ai chi ch'uan uses the five elements to designate different directions, positions or footwork patterns. Either forward, backward, left, right and centre, or three steps forward (attack) and two steps back (retreat).[11]

The Five Steps (五步 wǔ bù):

- Jìn bù (進步, in simplified characters 进步) Forward step

- Tùi bù (退步) Backward step

- Zǔo gù (左顧, in simplified characters 左顾) Left step

- Yòu pàn (右盼) Right step

- Zhōng dìng (中定) Central position, balance, equilibrium

Xingyiquan uses the five elements metaphorically to represent five different states of combat.

| Movement | Fist | Chinese | Pinyin | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal | Splitting | 劈 | Pī | To split like an axe chopping up and over |

| Water | Drilling | 鑽 / 钻 | Zuān | Drilling forward horizontally like a geyser |

| Wood | Crushing | 崩 | Bēng | To collapse, as a building collapsing in on itself |

| Fire | Pounding | 炮 | Pào | Exploding outward like a cannon while blocking |

| Earth | Crossing | 橫 / 横 | Héng | Crossing across the line of attack while turning over |

Tea ceremony[edit source]

There are spring, summer, fall, and winter teas. The perennial tea ceremony includes four tea settings (茶席) and a tea master (司茶). Each tea setting is arranged and stands for the four directions (North, South, East, and West). A vase of the seasons' flowers is put on the tea table. The tea settings are:

- Earth, 香 (Incense), yellow, center, up and down

- Wood, 春風 (Spring Wind), green, east

- Fire, 夏露 (Summer Dew), red, south

- Metal, 秋籟 (Fall Sounds), white, west

- Water, 冬陽 (Winter Sunshine) black/blue, north

See also[edit source]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wu Xing. |

10)

Warring States period

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

| Warring States period | |||

|---|---|---|---|

"Warring States" in seal script (top), Traditional (middle), and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters

| |||

| Traditional Chinese | 戰國時代 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 战国时代 | ||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhànguó Shídài | ||

| Literal meaning | "Warring States era" | ||

| |||

| History of China | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCIENT | |||||||

| Neolithic c. 8500 – c. 2070 BC | |||||||

| Xia c. 2070 – c. 1600 BC | |||||||

| Shang c. 1600 – c. 1046 BC | |||||||

| Zhou c. 1046 – 256 BC | |||||||

| Western Zhou | |||||||

| Eastern Zhou | |||||||

| Spring and Autumn | |||||||

| Warring States | |||||||

| IMPERIAL | |||||||

| Qin 221–207 BC | |||||||

| Han 202 BC – 220 AD | |||||||

| Western Han | |||||||

| Xin | |||||||

| Eastern Han | |||||||

| Three Kingdoms 220–280 | |||||||

| Wei, Shu and Wu | |||||||

| Jin 266–420 | |||||||

| Western Jin | |||||||

| Eastern Jin | Sixteen Kingdoms | ||||||

| Northern and Southern dynasties 420–589 | |||||||

| Sui 581–618 | |||||||

| Tang 618–907 | |||||||

| (Wu Zhou 690–705) | |||||||

| Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms 907–979 | Liao 916–1125 | ||||||

| Song 960–1279 | |||||||

| Northern Song | Western Xia | ||||||

| Southern Song | Jin | ||||||

| Yuan 1271–1368 | |||||||

| Ming 1368–1644 | |||||||

| Qing 1636–1912 | |||||||

| MODERN | |||||||

| Republic of China 1912–1949 | |||||||

| People's Republic of China 1949–present | |||||||

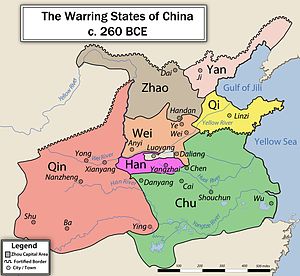

The Warring States period (simplified Chinese: 战国时代; traditional Chinese: 戰國時代; pinyin: Zhànguó Shídài) was an era in ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded with the Qin wars of conquest that saw the annexation of all other contender states, which ultimately led to the Qin state's victory in 221 BC as the first unified Chinese empire, known as the Qin dynasty.

Although different scholars point toward different dates ranging from 481 BC to 403 BC as the true beginning of the Warring States, Sima Qian's choice of 475 BC is the most often cited. The Warring States era also overlaps with the second half of the Eastern Zhou dynasty, though the Chinese sovereign, known as the king of Zhou, ruled merely as a figurehead and served as a backdrop against the machinations of the warring states.

The "Warring States Period" derives its name from the Record of the Warring States, a work compiled early in the Han dynasty.

11)

"The subject deals with the story of Laotzu riding an ox through a pass. It is said that with the fall of the Chou dynasty, Laotzu decided to travel west through the Han Valley Pass. The Pass Commissioner, Yin-hsi, noticed a trail of vapor emanating from the east, deducing that a sage must be approaching. Not long after, Laotzu riding his ox indeed appeared and, at the request of Yin-hsi, wrote down his famous Tao-te ching, leaving afterwards. This story thus became associated with auspiciousness."

12)

Cao Cao

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

| Cao Cao 曹操 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A Ming dynasty illustration of Cao Cao in the Sancai Tuhui.

| |||||||||||||

| King of Wei (魏王) | |||||||||||||

| Tenure | 216 – 15 March 220 | ||||||||||||

| Successor | Cao Pi | ||||||||||||

| Duke of Wei (魏公) | |||||||||||||

| Tenure | 213–216 | ||||||||||||

| Imperial Chancellor (丞相) | |||||||||||||

| Tenure | 208 – 15 March 220 | ||||||||||||

| Successor | Cao Pi | ||||||||||||

| Minister of Works (司空) | |||||||||||||

| Tenure | 196–208 | ||||||||||||

| Born | c. 155 Qiao County, Pei State, Han Empire | ||||||||||||

| Died | 15 March 220 (aged 64–65) Luoyang, Han Empire | ||||||||||||

| Burial | 11 April 220 | ||||||||||||

| Consorts | Empress Wuxuan | ||||||||||||

| Issue | Cao Ang Cao Pi Cao Zhang Cao Zhi Cao Xiong Cao Shuo Cao Chong Cao Ju Cao Yu Cao Lin Cao Gun Cao Xuan Cao Jun Cao Ju Cao Gan Cao Shang Cao Biao Cao Qin Cao Cheng Cao Zheng Cao Jing Cao Jun Cao Ji Cao Hui Cao Mao Cao Xian Cao Jie Cao Hua Princess Anyang Princess Jin Princess Qinghe | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Father | Cao Song | ||||||||||||

| Mother | Lady Ding | ||||||||||||

| Cao Cao | |||

|---|---|---|---|

"Cao Cao" in Chinese characters

| |||

| Chinese | 曹操 | ||

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese legalism |

|---|

|

Cao Cao ( pronunciation (help·info); [tsʰǎu tsʰáu]; Chinese: 曹操; c. 155 – 15 March 220),[1] courtesy name Mengde, was a warlord and the penultimate Chancellor of the Eastern Han dynasty who rose to great power in the final years of the dynasty. As one of the central figures of the Three Kingdoms period, he laid the foundations for what was to become the state of Cao Wei and ultimately the Jin dynasty, and was posthumously honoured as "Emperor Wu of Wei". He is often portrayed as a cruel and merciless tyrant in subsequent literature; however, he has also been praised as a brilliant ruler and military genius who treated his subordinates like his family.

pronunciation (help·info); [tsʰǎu tsʰáu]; Chinese: 曹操; c. 155 – 15 March 220),[1] courtesy name Mengde, was a warlord and the penultimate Chancellor of the Eastern Han dynasty who rose to great power in the final years of the dynasty. As one of the central figures of the Three Kingdoms period, he laid the foundations for what was to become the state of Cao Wei and ultimately the Jin dynasty, and was posthumously honoured as "Emperor Wu of Wei". He is often portrayed as a cruel and merciless tyrant in subsequent literature; however, he has also been praised as a brilliant ruler and military genius who treated his subordinates like his family.

During the fall of the Eastern Han dynasty, Cao Cao was able to secure the most populated and prosperous cities of the central plains and northern China. Cao Cao had much success as the Han chancellor, but his handling of the Han Emperor Xian was heavily criticised and resulted in a continued and then escalated civil war. Opposition directly gathered around warlords Liu Bei and Sun Quan, whom Cao Cao was unable to quell.

13)

Sichuan

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Sichuan ( 四川; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan) is a landlocked province in Southwest China occupying most of the Sichuan Basin and the easternmost part of the Tibetan Plateau between the Jinsha River on the west, the Daba Mountains in the north, and the Yungui Plateau to the south. Sichuan's capital city is Chengdu. The population of Sichuan stands at 81 million.

四川; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan) is a landlocked province in Southwest China occupying most of the Sichuan Basin and the easternmost part of the Tibetan Plateau between the Jinsha River on the west, the Daba Mountains in the north, and the Yungui Plateau to the south. Sichuan's capital city is Chengdu. The population of Sichuan stands at 81 million.

In antiquity, Sichuan was the home of the ancient states of Ba and Shu. Their conquest by Qin strengthened it and paved the way for the Qin Shi Huang's unification of China under the Qin dynasty. During the Three Kingdoms era, Liu Bei's Shu was based in Sichuan. The area was devastated in the 17th century by Zhang Xianzhong's rebellion and the area's subsequent Manchu conquest, but recovered to become one of China's most productive areas by the 19th century. During World War II, Chongqing served as the temporary capital of the Republic of China, making it the focus of Japanese bombing. It was one of the last mainland areas to fall to the Communists during the Chinese Civil War and was divided into four parts from 1949 to 1952, with Chongqing restored two years later. It suffered gravely during the Great Chinese Famine of 1959–61 but remained China's most populous province until Chongqing Municipality was again separated from it in 1997.

The people of Sichuan speak a unique form of Mandarin, which took shape during the area's repopulation under the Ming. The family of dialects is now spoken by about 120 million people, which would make it the 10th most spoken language in the world if counted separately. The area's warm damp climate long caused Chinese medicine to advocate spicy dishes; the native Sichuan pepper helped to form modern Sichuan cuisine, whose dishes—including Kung Pao chicken and Mapo tofu—have become staples of Chinese cuisine around the world.

14)

Shu Han

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (January 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Shu Han

蜀漢

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 221–263 | |||||||||

The territories of Shu Han (in light pink), as of 262 A.D..

| |||||||||

| Capital | Chengdu | ||||||||

| Common languages | Ba-Shu Chinese | ||||||||

| Religion | Taoism, Confucianism, Chinese folk religion | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||

• 221–223

| Liu Bei | ||||||||

• 223–263

| Liu Shan | ||||||||

| Historical era | Three Kingdoms | ||||||||

• Established

| 221 | ||||||||

| 263 | |||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 221[1]

| 900,000 | ||||||||

• 263[1]

| 1,082,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | Chinese coin, Chinese cash | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | China Myanmar | ||||||||

| Shu Han | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 蜀漢 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 蜀汉 | ||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Shǔ Hàn | ||

| |||

Shu or Shu Han ([ʂù xân] ( listen); 221–263) was one of the three major states that competed for supremacy over China in the Three Kingdoms period (220–280). The state was based in the area around present-day Sichuan and Chongqing, which was historically known as "Shu" after an earlier state in Sichuan named Shu. Shu Han's founder Liu Bei had named his state "Han" as he considered it the legitimate successor to the Han dynasty, while "Shu" is added to the name as a geographical prefix to differentiate it from the many "Han" states throughout Chinese history.

listen); 221–263) was one of the three major states that competed for supremacy over China in the Three Kingdoms period (220–280). The state was based in the area around present-day Sichuan and Chongqing, which was historically known as "Shu" after an earlier state in Sichuan named Shu. Shu Han's founder Liu Bei had named his state "Han" as he considered it the legitimate successor to the Han dynasty, while "Shu" is added to the name as a geographical prefix to differentiate it from the many "Han" states throughout Chinese history.

15)

Quanzhen School

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Daoism |

|---|

|

| Quanzhen | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 全眞 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 全真 | ||

| Literal meaning | All True | ||

| |||

The Quanzhen School is a branch of Taoism that originated in Northern China under the Jin dynasty (1115–1234).[1] One of its founders was the Taoist Wang Chongyang, who lived in the early Jin. When the Mongols invaded the Song dynasty (960–1279) in 1254, the Quanzhen Taoists exerted great effort in keeping the peace, thus saving thousands of lives, particularly among those of Han Chinese descent.

16)

Zhengyi Dao

| Part of a series on |

| Daoism |

|---|

|

Zhengyi Dao (Chinese: 正一道; pinyin: Zheng Yi Dào) or the Way of Orthodox Unity is a Chinese Daoist movement that emerged during the Tang dynasty as a transformation of the earlier Tianshi Dao movement. Like Tianshi Dao, the leader of Zhengyi Daoism was known as the Celestial Master.

17)

Neo-Confucianism

(Redirected from Neo-Confucian)

| Neo-Confucianism | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 宋明理學 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 宋明理学 | ||

| Literal meaning | "Song-Ming [dynasty] rational idealism" | ||

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| Confucianism |

|---|

|

Neo-Confucianism (Chinese: 宋明理學; pinyin: Sòng-Míng lǐxué, often shortened to lixue 理學) is a moral, ethical, and metaphysical Chinese philosophy influenced by Confucianism, and originated with Han Yu and Li Ao (772–841) in the Tang Dynasty, and became prominent during the Song and Ming dynasties.

Neo-Confucianism could have been an attempt to create a more rationalist and secular form of Confucianism by rejecting superstitious and mystical elements of Taoism and Buddhism that had influenced Confucianism during and after the Han Dynasty.[1] Although the neo-Confucianists were critical of Taoism and Buddhism, the two did have an influence on the philosophy, and the neo-Confucianists borrowed terms and concepts. However, unlike the Buddhists and Taoists, who saw metaphysics as a catalyst for spiritual development, religious enlightenment, and immortality, the neo-Confucanists used metaphysics as a guide for developing a rationalist ethical philosophy.[2][3]

18)

Daozang

| Part of a series on |

| Daoism |

|---|

|

Daozang (Chinese: 道藏; pinyin: Dàozàng; Wade-Giles: Tao Tsang), meaning "Taoist Canon", consists of around 1,400 texts that were collected c. 400 (after the Dao De Jing and Zhuang Zi which are the core Taoist texts). They were collected by Taoist monks of the period in an attempt to bring together all of the teachings of Taoism, including all the commentaries and expositions of the various masters from the original teachings found in the Tao Te Ching and Zhuangzi. It was split into Three Grottoes, which mirrors the Buddhist Tripitaka (three baskets) division. These three divisions were based on the main focus of Taoism in Southern China during the time it was made, namely; meditation, ritual, and exorcism.

These Three Grottoes were used as levels for the initiation of Taoist masters, from lowest (exorcism) to highest (meditation).

As well as the Three Grottoes there were Four Supplements that were added to the Canon c. 500. These were mainly taken from older core Taoist texts (e.g. Tao Te Jing) apart from one which was taken from an already established and separate philosophy known as Tianshi Dao (Way of the Heavenly Masters).

Although the above can give the appearance that the Canon is highly organized, this is far from the truth. Although the present-day Canon does preserve the core divisions, there are substantial forks in the arrangement due to the later addition of commentaries, revelations and texts elaborating upon the core divisions.

19)

White Cloud Temple

(Redirected from White Cloud Monastery)

| White Cloud Temple | |

|---|---|

The archway in front of the entrance to the temple site

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Taoism |

| Location | |

| Location | Beijing, China |

| Geographic coordinates | 39°53′56″N 116°20′17″ECoordinates: 39°53′56″N 116°20′17″E |

| Architecture | |

| Completed | 14th Century Ming dynasty |

| White Cloud Temple | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 白雲觀 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 白云观 | ||

| Literal meaning | Temple of the White Cloud(s) | ||

| |||

| Tianchang Temple | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 天長觀 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 天长观 | ||

| Literal meaning | Temple of Heavenly Perpetuity | ||

| |||

| Changchun Temple | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 長春宮 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 长春宫 | ||

| Literal meaning | Palace of Eternal Spring Palace of Master Changchun | ||

| |||

The White Cloud Temple, also known as Baiyun Temple or the Abbey or Monastery of the White Clouds, is a Taoist temple and monastery located in Beijing, China. It is one of "The Three Great Ancestral Courts" of the Quanzhen School of Taoism and is titled "The First Temple under Heaven".

20)

Chinese Taoist Association

| Part of a series on |

| Daoism |

|---|

|

Chinese Taoist Association (CTA ; Chinese: 中国道教协会), founded in April 1957, is the main association of Taoism in the People's Republic of China. It is recognized as one of the main religious associations in the People's Republic of China, and is overseen by the State Administration for Religious Affairs. Dozens of regional and local Taoist associations are included in this overarching group, which is encouraged by the government to be a bridge between Chinese Taoists and the government, to encourage a patriotic merger between Taoism and government initiatives.[1] The group also disseminates information on traditional Taoist topics, including forums and conferences. The association was a major sponsor of the 2007 International Forum on the Tao Te Ching.[2] The Chinese Taoist Association advocates the recompensation of losses inflicted on Taoism by the Cultural Revolution. Taoism was banned for several years in the People's Republic of China during that period.[citation needed]

Taoist practitioners in China are required to register with the Chinese Taoist Association in order to be granted recognition and official protection. The CTA exercises control over religious doctrine and personnel, and dictates the proper interpretation of Taoist doctrine.[3] It also encourages Taoist practitioners to support the Communist Party and the state. For example, a Taoist scripture reading class held by the CTA in November 2010 required participants to ‘‘fervently love the socialist motherland [and] uphold the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party.’’[3] The central government of China has supported and encouraged the Association, along with other official religious groups, in promoting the "harmonious society" initiative of Communist Party General Secretary Hu Jintao.[4]

21)

Wu wei

| Wu wei | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||

| Simplified Chinese | 无为 | ||

| Traditional Chinese | 無爲 | ||

| |||

| Vietnamese name | |||

| Vietnamese | Vô vi | ||

| Korean name | |||

| Hangul | 무위 | ||

| Hanja | 無爲 | ||

| |||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 無為 | ||

| Hiragana | むい | ||

| |||

Wu wei (無爲) is a concept literally meaning "inexertion" or "inaction".[1]:p7 Wu wei emerged in the Spring and Autumn period, and from Confucianism, to become an important concept in Chinese statecraft and Taoism, and was most commonly used to refer to an ideal form of government[1]:p6 including the behavior of the emperor. Describing a state of unconflicting personal harmony, free-flowing spontaneity and savoir-faire, it generally also more properly denotes a state of spirit or mind, and in Confucianism accords with conventional morality. Sinologist Jean François Billeter describes it as a "state of perfect knowledge of the reality of the situation, perfect efficaciousness and the realization of a perfect economy of energy", which in practice Edward Slingerland qualifies as a "set of ("transformed") dispositions (including physical bearing)... conforming with the normative order."[1]:p7

22)

Ontology

(Redirected from Ontological)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Ontology is the philosophical study of being. More broadly, it studies concepts that directly relate to being, in particular becoming, existence, reality, as well as the basic categories of being and their relations.[1] Traditionally listed as a part of the major branch of philosophy known as metaphysics, ontology often deals with questions concerning what entities exist or may be said to exist and how such entities may be grouped, related within a hierarchy, and subdivided according to similarities and differences.

23)

Arthur Waley

Arthur Waley

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

A portrait of Waley by Ray Strachey

| |||

| Born | 19 August 1889 | ||

| Died | 27 June 1966 (aged 76)

London, England

| ||

| Resting place | Highgate Cemetery | ||

| Alma mater | Cambridge University (did not graduate) | ||

| Known for | Chinese/Japanese translations | ||

| Chinese name | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 亞瑟・偉利 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 亚瑟・伟利 | ||

| |||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kana | アーサー・ウェイリ | ||

| |||

Arthur David Waley CH CBE (born Arthur David Schloss, 19 August 1889 – 27 June 1966) was an English orientalist and sinologist who achieved both popular and scholarly acclaim for his translations of Chinese and Japanese poetry. Among his honours were the CBE in 1952, the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry in 1953, and he was invested as a Companion of Honour in 1956.[1]

Although highly learned, Waley avoided academic posts and most often wrote for a general audience. He chose not to be a specialist but to translate a wide and personal range of classical literature. Starting in the 1910s and continuing steadily almost until his death in 1966, these translations started with poetry, such as A Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems (1918) and Japanese Poetry: The Uta (1919), then an equally wide range of novels, such as The Tale of Genji (1925–26), an 11th-century Japanese work, and Monkey, from 16th-century China. Waley also presented and translated Chinese philosophy, wrote biographies of literary figures, and maintained a lifelong interest in both Asian and Western paintings.

A recent evaluation called Waley "the great transmitter of the high literary cultures of China and Japan to the English-reading general public; the ambassador from East to West in the first half of the 20th century", and went on to say that he was "self-taught, but reached remarkable levels of fluency, even erudition, in both languages. It was a unique achievement, possible (as he himself later noted) only in that time, and unlikely to be repeated."[2]

-----------------------------------

https://slideplayer.com/slide/13412885/

Comments

Post a Comment